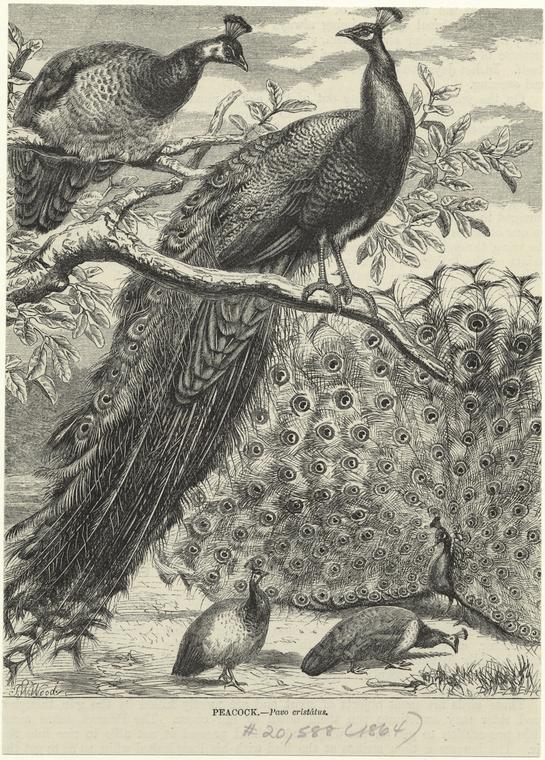

The peacock carries a magnificent iridescent tail, which amounts to more than 60% of its total body length. Its feathers fan out in a display of an eye-like form made of blue or green, gold red and purple shimmer. To attract females (peahens), the male peacock flares his feathers open, displaying his glimmering baroque decoration. Why would a peacock carry such a large over-burdening aesthetic display, possibly putting itself in danger from its predators?

The peacock carries a magnificent iridescent tail, which amounts to more than 60% of its total body length. Its feathers fan out in a display of an eye-like form made of blue or green, gold red and purple shimmer. To attract females (peahens), the male peacock flares his feathers open, displaying his glimmering baroque decoration. Why would a peacock carry such a large over-burdening aesthetic display, possibly putting itself in danger from its predators?

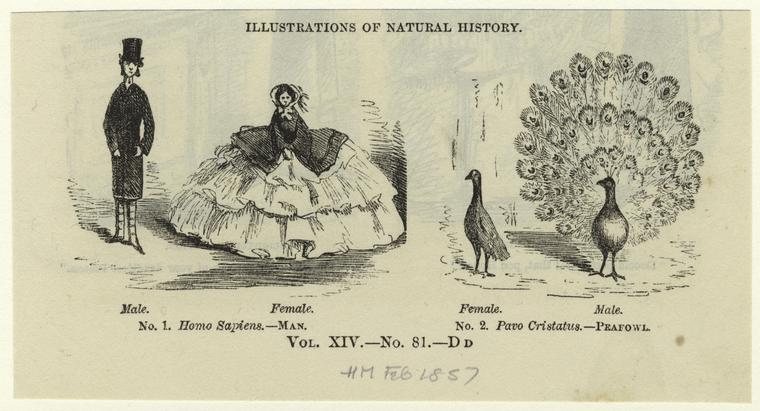

Most animals and humans are bilaterally symmetrical: they have two or more symmetrical limbs, two eyes, two nostrils and so on. The more symmetrical the face and body appear, the less of an indication that an underlying genetic screw-up, or a physical/mental handicap exists. This evolutionary parameter plays a large role in sexual attraction, and in our assessment of beauty—we tend to consider people who appear most symmetrical as beautiful. Therefore, the best-ornamented peacock male will have the possibility of attracting the most maternaly-inclined female. Her qualities coupled with his health and fitness can offer the best opportunity for a survivor offspring.

The peacock’s long and handsome tail not only signals to peahens that he is healthy and carries good genes, but more importantly, that he is faster and quicker in battle than his predators in spite of his encumbering train. In other words: since carrying such a big tail puts the peacock’s life at stake, then his signaling of strength and health must be reliable and honest. This hypothesis of honest signaling1 is known as the handicap principle. It suggests that the signified must be costly to the signaling animal to be reliable.

The system of signaling strength and quality (for the purpose of sexual selection) is often discussed in relation to art and its history as a system of signals in humans. Art’s value2 is created by a mechanism that includes curators, critics, dealers and collectors, and the term value doesn’t always imply monetary exchange. However, when considering minimalist trash art, I find a gap between the way the work is discussed and what is actually there.

The system of signaling strength and quality (for the purpose of sexual selection) is often discussed in relation to art and its history as a system of signals in humans. Art’s value2 is created by a mechanism that includes curators, critics, dealers and collectors, and the term value doesn’t always imply monetary exchange. However, when considering minimalist trash art, I find a gap between the way the work is discussed and what is actually there.

[ I took this photo in a run-down building on Governor’s Island. It’s not trash art yet, but if I ripped out the carpet and placed it in a white cube, it could be a good contender ]

[ I took this photo in a run-down building on Governor’s Island. It’s not trash art yet, but if I ripped out the carpet and placed it in a white cube, it could be a good contender ]

I also find it curious that artists who work with trash art manage to be presented by commercial galleries, and have their work sold for substantial prices. It would seem rather conservative of me, and perhaps a bit ignorant to try and discredit their work. I would instead explain the works’ lineage and propose a question: since we live in a capitalist society, which relies heavily on private funding, why do collectors buy art that is made of rearranged trash?

Artists who’s work can be categorized as trash art, often point to Richard Tuttle as their heritage. Tuttle’s 1975 survey exhibition at the Whitney, received a scathing review by Hilton Kramer, the art critic for The NY Times who wrote, “in Mr. Tuttle’s work, less is unmistakably less…One is tempted to say, art is concerned, less has never been as less than this.” This was a monumental moment in American history of art. Due to the bad review, Marcia Tucker—the show’s curator—lost her job and started a new museum: the New Museum.

This reaction to the work and reaction to that reaction led to the endorsement of minimalist trash art by the (new) institution. I should add that I see a difference between Tuttle’s work and the Modernist processes that brought to the development of European Bricolage including Kurt Schwitters’ pieces entitled Merzbau. I attribute this difference to the reliance of the American system on private funding, although admittedly, the European system is also capitalist in nature. The circle of belief2 in the United States is tilted in the direction of the collector/buyer rather than to the learnt curator, critic or art historian and not in the direction of public funding for equal right exploration. The European system, however, allows a space for artists and arts organizations to operate, a space that is independent of the sways of the art market.

Art is a form of conspicuous consumption and the ultimate display of wealth in humans. If we follow the idea behind the handicap principal, that the peacock’s tail is a signifier for strength, then spending lots of money on something that looks worthless is the ultimate human signifier for wealth. It means the collector’s actions involve honest signaling because they didn’t buy something that looks well-made and possibly commercial, but something that seemingly does not justify a price at all. Additionally, not only does owning trash art speak to the collector’s abundance of funds, but it implies the collector is an influential person himself who has the insider’s scoop, and is someone who gets it.

This could all be fine. The trouble is that the system at play influences what artists make. And instead of getting to the heart of what matters, they fall into the trap of internal games. Is the work as charged and engaging as can be, or is it only alive by power of opposition?

Orit Ben-Shitrit

2010

[ This unrelated photo is from a parking lot in Tel Aviv. Whoever made this mark on the wall, might have been concerned that a driver might occupy a bigger parking spot than intended… ]

[ This unrelated photo is from a parking lot in Tel Aviv. Whoever made this mark on the wall, might have been concerned that a driver might occupy a bigger parking spot than intended… ]

1 Helena Cronin, The Ant and the Peacock: Altruism and Sexual Selection from Darwin to Today.

2 Pierre Bourdieu, The Field of Cultural Production, Essays on Art and Literature, Edited and Introduced by Randal Johnson. 2: The Production of Belief: Contribution to an Economy of Symbolic Goods.